Therefore, utilizing biblical verification, early church leaders arduously strived to compose and communicate the supernatural relationship of Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit, which they eventually termed, “The Trinity” - the Latin word for “Three-ness.” Specifically, the Church Fathers concluded that God exists as a single deity with three separate but permanently connected persons in his ontology. So, though one God, he is also differentiated within himself to accomplish his divine will in Heaven, the universe, and on earth. He is not three separated entities or beings; nor is he a single person revealing himself in three forms (which the heresy, Modalism, contends). Paradoxically, God's persons are simultaneous and not consecutive, and, via “Perichoresis,” they “dance around each other,” focusing on specific activities although still enveloping each other and each other's work. Though not specifically referenced in the Bible by word, the reality of the Trinity can be observed in both the Hebrew and Greek scriptures, although it is more noticeable in the New Testament writers' assertions and explanations.

To preserve the original message and meaning of Christianity, several Christian communities created creeds (a formal statement of religious belief) to help define and defend Christian doctrine and characteristics. Many consider Romans 10:8-9 to be the first Christian creed - “The word of faith we are proclaiming: That if you confess with your mouth, 'Jesus is Lord,' and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.”

Christian tradition suggests that, later on, the Jesus' Disciples wrote the Apostles Creed (c. 150 CE) after Jesus' crucifixion, although modern scholarship puts the date to be post 2nd century CE. In this ancient creed, it presents God as the creator, discusses Jesus' birth, death, resurrection, and ascension into Heaven. It also references the Holy Spirit and his communication with the World (although it omits an official discussion of the Trinity), and ends with an explanation of the Church, its saints, and the afterlife.

Under the supervision of Emperor Constantine I, the Nicene Creed (325 CE) was composed by an ecumenical council, which was and is accepted as authoritative by most Christian groups, but not by the Eastern Orthodox Church (at least, the second version in 381 CE is rejected for adding in the Filioque Clause—"And the Son"). It describes the pre-existence of Jesus Christ, his role in the future judgment of humanity, how Jesus is "homoousis" - of one substance with God, how/why the Holy Spirit is to be worshipped as part of the holy family, discusses the requirement of baptism, and minimizes the earthly ministry of Jesus Christ, interestingly.

Although there are others, the Athanasian Creed (328 CE) is important as it deals mainly with the Trinity, and pushes back against the heresies of the day: Arianism, Docetism, Modalism, and Monophytism. It expands upon the Nicene Creed and promotes a more exclusive understanding of salvation and eternal rejection for non-believers.

The followers of Jesus Christ would finally see a reprieve from their centuries-long struggles to worship Jesus Christ as their king and Lord in Roman society under Emperor Flavius Valerius Constantinus, also known as Constantine I the Great (c. 280-337 CE). Contrary to his predecessors, and perhaps because of the havoc and weakening that ensued after Diocletian's abdication of the Imperial throne in 305 CE, Constantine saw value (and possibly truth) in the Christian way and, once in power, took steps to remove all former legal restrictions on Christianity. Specifically, in the Edict of Milan, composed in 313 CE, Constantine offered citizens of the Empire new freedoms and protections from centuries-old bigoted edicts. No doubt, 4th-century CE Christians felt a peace like none before as they read (or heard) in the Edict of Milan,

Although Constantine's “conversion” to Christianity is controversial (was it for personal or political reasons?), the future sole emperor later spoke of a dream that he had the night before his pivotal battle with Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge (312 CE) wherein God told him to have the Christian “Chi-Rho” monogram painted on his soldiers' shields to ensure success. Considering that Maxentius' forces were double that of Constantine's, Constantine's chances were slim, at best. Whether due to desperation or blind faith, he purportedly submitted to the instructions in his dream (although early reports of the battle omit the divine vision telling him, "In hoc signo vinces" - "In this sign conquer"), carried a new banner of allegiance into battle, and won the day.

His victory achieved, and with the drowning of Maxentius earlier in battle, Constantine went on to become sole emperor of an undivided empire in 324 CE. An apt and inspirational administrator, he set forth to reform the great Roman Empire that had been dwindling down for decades, with God at his back. More so, he became a patron of Christianity and its church, appointing Christians to high political office and giving them the same rights as other Pagan political officers, paving the way for Christianity to lead society - not be dragged down or crushed by it.

By the 5th century CE, Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman Empire, leading to a dramatic change in how the faith played out in greater society. This caused a shift in Christianity from private to public worship; from a distinctly Jewish character to one more aligned with the Gentiles; from an individual matter to more of a community affair; from a seeker-driven faith to an exclusively chosen body of believers; from a looser, more informal structure to that of distinct strata of operation and authority; and from gender empowering to more specific gender-specific limitations. Additionally, Christian leaders had to figure out how Christianity integrated with Roman law and government, dealt with barbarian peoples, and still maintained the essence of Jesus' teachings and missions for his followers.

The next two centuries of Christianity would see the development of the episcopacy and the rise of a religious aristocracy - the clergy and laity, the papacy, the priesthood of some, not all, believers. Furthermore, where previously riches were a sign of greed and exploitation, once endorsed and involved with the emperor, now riches were seen in a more favorable light. An even greater juxtaposition was the shift from Christian pacifism to militarianism (also no doubt due to the syncretization of Christianity into secular society). Theologically, there was a move away from Millennialism and the Second Coming of Christ to a more practical, earthly understanding of the kingdom of God; the enforcement of clerical abstinence and the condemnation of simony; the addition of Purgatory to key medieval church dogma; the establishment of the Sacraments, which institutionally demonstrated the outward signs of God's inward grace in the lives of his followers; and the evolution of Christian monasticism throughout Europe and Africa.

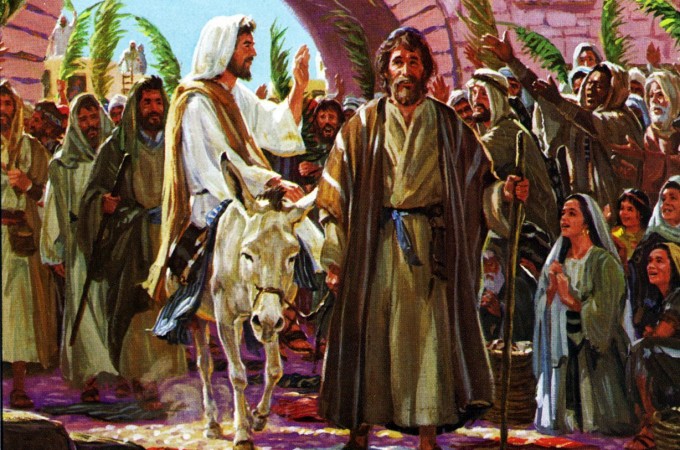

Some might consider such institutionalism contrary to the original Jesus movement; however, it is best to remember that, according to Christian scripture, Jesus was confirmed by Jewish scripture to be the prophesized Messiah, he taught regularly and enthusiastically in the Temple for years, he affirmed and participated in the numerous Jewish festivals and customs required of Judaism, and he became the perfect priest and sacrifice before God on humanity's behalf. Moreover, Jesus also established his Twelve Disciples to be official ambassadors of the Kingdom of God, to act as heralds of the new covenant between God and humanity. He also promised them that at the Final Judgment, they would be the ones to judge the tribes of Israel.

Yet, Jesus was quite adroit at making the best of all situations, whether personal or public, private or institutional, turning every situation into an opportunity to love God with all his heart, soul, and mind; and to love his neighbor as himself. He also called upon his believers to follow his loving model in reaching the world for God. As the Apostle Paul writes in Galatians, which includes one of the oldest self-definitions of Christianity, “Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ, who gave himself for our sins so that he might rescue us from the present evil age, according to the will of our God and Father, to whom be the glory forever more. Amen" (Galatians 1:3-5, NASB).

In the 20-plus centuries since the ministry of Jesus, many Christians have willingly and sacrificially tried to reach the world for God, to continue the great commandment of Jesus Christ in their own complicated lives, changing cultures, and imperfect ways - sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. This was true in the 1st century, CE, and, century after century, it is still a reality for the Christian movement, 2,000 years later.