John was the son of Zebedee, a Galilean fisherman, and Salome. John and his brother St. James were among the first disciples called by Jesus. In the Gospel According to Mark he is always mentioned after James and was no doubt the younger brother. His mother was among those women who ministered to the circle of disciples. James and John were called Boanerges, or “sons of thunder,” by Jesus, perhaps because of some character trait such as the zeal exemplified in Mark 9:38 and Luke 9:54, when John and James wanted to call down fire from heaven to punish the Samaritan towns that did not accept Jesus. John and his brother, together with St. Peter, formed an inner nucleus of intimate disciples. In the Fourth Gospel, ascribed by early tradition to John and known formally as the Gospel According to John, the sons of Zebedee are mentioned only once, as being at the shores of the Sea of Tiberias when the risen Lord appeared. Whether the “disciple whom Jesus loved” (who is never named) mentioned in this Gospel is to be identified with John (also not named) is not clear from the text.

John’s authoritative position in the church after the Resurrection is shown by his visit with St. Peter to Samaria to lay hands on the new converts there. It is to Peter, James (not the brother of John but “the brother of Jesus”), and John that St. Paul successfully submitted his conversion and mission for recognition. What position John held in the controversy concerning the admission of the Gentiles to the church is not known; the evidence is insufficient for a theory that the Johannine school was anti-Pauline—i.e., opposed to granting Gentiles membership in the church.

John’s subsequent history is obscure and passes into the uncertain mists of legend. At the end of the 2nd century, Polycrates, bishop of Ephesus, claims that John’s tomb is at Ephesus, identifies him with the beloved disciple, and adds that he “was a priest, wearing the sacerdotal plate, both martyr and teacher.” That John died in Ephesus is also stated by St. Irenaeus, bishop of Lyon circa 180 CE, who says John wrote his Gospel and letters at Ephesus and Revelation at Pátmos. During the 3rd century two rival sites at Ephesus claimed the honour of being the apostle’s grave. One eventually achieved official recognition, becoming a shrine in the 4th century. In the 6th century the healing power of dust from John’s tomb was famous (it is mentioned by the Frankish historian St. Gregory of Tours). At this time also, the church of Ephesus claimed to possess the autograph of the Fourth Gospel.

Legend was also active in the West, being especially stimulated by the passage in Mark 10:39, with its hints of John’s martyrdom. Tertullian, the 2nd-century North African theologian, reports that John was plunged into boiling oil from which he miraculously escaped unscathed. During the 7th century this scene was portrayed in the Lateran basilica and located in Rome by the Latin Gate, and the miracle is still celebrated in some traditions. In the original form of the apocryphal Acts of John (second half of the 2nd century) the apostle dies, but in later traditions he is assumed to have ascended to heaven like Enoch and Elijah. The work was condemned as a gnostic heresy in 787 CE. Another popular tradition, known to St. Augustine, declared that the earth over John’s grave heaved as if the apostle were still breathing.

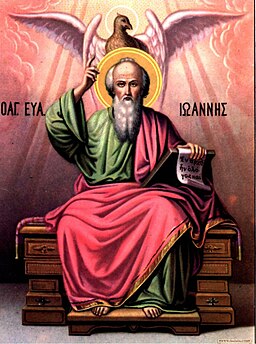

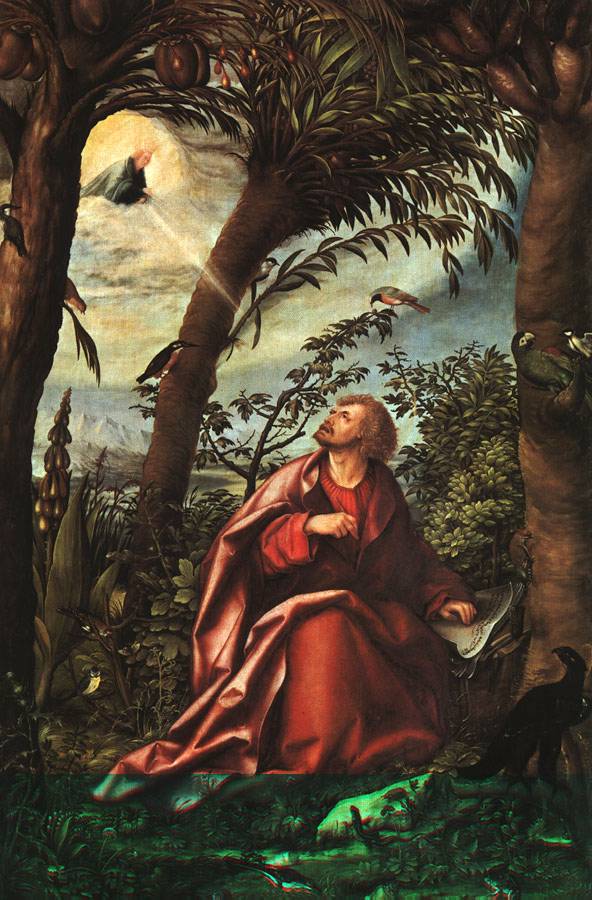

The legends that contributed most to medieval iconography are mainly derived from the apocryphal Acts of John. These Acts are also the source of the notion that John became a disciple as a very young man. Iconographically, the young beardless type is early (as in a 4th-century sarcophagus from Rome), and this type came to be preferred (though not exclusively) in the medieval West. In the Byzantine world the evangelist is portrayed as old, with long white beard and hair, usually carrying his Gospel. His symbol as an evangelist is an eagle. Because of the inspired visions of the book of Revelation, the Byzantine churches entitled him “the Theologian”; the title appears in Byzantine manuscripts of Revelation but not in manuscripts of the Gospel.

Acts of John, an apocryphal (noncanonical and unauthentic) Christian writing, composed about AD 180, purporting to be an account of the travels and miracles of St. John the Evangelist. Photius, the 9th-century patriarch of Constantinople, identified the author of the Acts of John as Leucius Charinus, otherwise unknown. The book reflects the heretical views of early Christian Docetists, who denied the reality of Christ’s physical body and attributed to it only the appearance of materiality. The Acts of John likewise has a hymn containing formulas to evade demons who, according to Gnostic teachings, could impede one’s journey to heaven. The book was condemned by the second Council of Nicaea, in AD 787, because of its subversion of orthodox Christian teachings.

The book comprises two main parts, the first of which (chapters 2–3) contains moral admonitions (but no visions or symbolism) in individual letters addressed to the seven Christian churches of Asia Minor. In the second part (chapters 4–22:5), visions, allegories, and symbols (to a great extent unexplained) so pervade the text that exegetes necessarily differ in their interpretations. Many scholars, however, agree that Revelation is not simply an abstract spiritual allegory divorced from historical events, nor merely a prophecy concerning the final upheaval at the end of the world, couched in obscure language. Rather, it deals with a contemporary crisis of faith, probably brought on by Roman persecutions. Christians are consequently exhorted to remain steadfast in their faith and to hold firmly to the hope that God will ultimately be victorious over his (and their) enemies. Because such a view presents current problems in an eschatological context, the message of Revelation also becomes relevant to future generations of Christians who, Christ forewarned, would likewise suffer persecution. The victory of God over Satan and his Antichrist (in this case, the perseverance of Christians in the face of Roman persecution) typifies similar victories over evil in ages still to come and God’s final victory at the end of time.

The First Letter of John was apparently addressed to a group of churches where “false prophets,” denounced as Antichrist, denied the Incarnation of Jesus and caused a secession so substantial that the orthodox remnant was sadly depleted. The faithful were deeply disturbed that the heresy found favour among pagans, and they apparently felt inferior because those who had left their midst claimed to have profound mystical experiences. The heretics asserted that they possessed perfection, were “born of God,” and were without sin. By placing themselves above the Commandments, they in fact sanctioned moral laxity. John’s letter thus urges the Christian community to hold fast to what they had been taught and to repudiate heretical teachings. Christians are exhorted to persevere in leading a moral life, which meant imitating Christ by keeping the Commandments, especially that of loving one another. The spirit of the letter closely parallels that of the Gospel According to John.